Two men came to Jesus, each with a request. One man was blind and poor, and wanted to see; the other was rich and sighted, and wanted eternal life.

Two men came to Jesus, each with a request. One man was blind and poor, and wanted to see; the other was rich and sighted, and wanted eternal life.

Both requests were good and right, and Jesus offered answers to both. So why did one man walk away praising God and the other walked away sad?

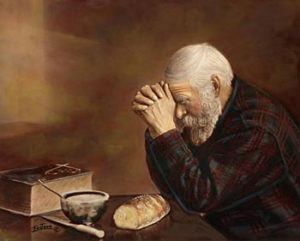

The difference between the two men was not in their wealth, but their heart. Yes, the blind man was poor; unable to see, his only income was the coins he begged from passersby at the city gates. Yet his poverty went deeper than his wallet. Downtrodden and outcast, all that his blind eyes could see was the rejection of those walking past him each day. And it was in this poverty of spirit that he cried out, “Jesus, Son of David, have mercy on me!” His request was both simple and impossible: I want to see.

The rich man may well have been one of those who tossed a few coins at the nameless, faceless beggars he daily rode by. Doubtless honored both for business savvy and his commandment-keeping righteousness, his request was no less honorable than the blind man’s: What must I do to inherit eternal life?

Though both petitions were good, the difference between them was stark. Where the blind man knew he was could do nothing to bring about his own healing, the rich man believed his prayer could be answered by some good deed, some noble gesture, some further mark of his own power and wealth and righteousness. His perfect eyes and fat money-purse blinded him to the poverty of his own soul.

Jesus answered both men’s requests just as they wanted him to: He did for the blind man what he knew he could not do for himself; and he gave the wealthy man a very simple task – a good deed that was very do-able yet proved impossible for the seeker of life.

There is a deep irony in these two encounters (read them in Luke 18:18-43): a penniless blind man sees his poverty, and purchases by his faith the new eyes that no king could ever afford. Across town a wealthy man, blind to his own destitution, refuses to trade his affluence for the only thing that could make him truly rich.

It is easy to read these stories in the Bible, to celebrate the healing of the one and groan at the obstinacy of the other. But God does not want us to merely read, cheer, and groan. He wants us to see ourselves in His Word, to decide how we will respond. Who are you?

Are you the man without eyes, convinced of your unworthiness and the impossibility of your situation? Or are you the one with both eyes and money, wondering what else you can do to earn God’s favor and presence?

Will you come to God in helpless faith, pleading for mercy first and sight second? Or do you come with wallet open, looking for yet another spiritual tax deduction?

Will you walk away with Jesus, glorifying God? Or will you just walk away, sadly looking for an easier way?

Last week, amidst all the outcry against zoos and irresponsible parents after an endangered gorilla was killed, I

Last week, amidst all the outcry against zoos and irresponsible parents after an endangered gorilla was killed, I