I, the LORD, will make a New Covenant, not like the one I made before. I will write my instruction on their hearts; I will be their God and they shall be my people. They will all know me, and I will forgive and forget their sins. (from Jeremiah 31:31-34)

I, the LORD, will make a New Covenant, not like the one I made before. I will write my instruction on their hearts; I will be their God and they shall be my people. They will all know me, and I will forgive and forget their sins. (from Jeremiah 31:31-34)

I’ve been reflecting lately on the New Covenant. As a pastor, it has been important to me because each time I have led my church in communion (aka the Lord’s Supper, the Eucharist), I’ve read Jesus’ words: “this cup is the new covenant in My blood” (see Luke 22:20). There is something powerful, something significant there, but as a 21st century Gentile, the ancient Jewish history is easily lost on me.

The part of that new covenant that is grabbing me right now are the words in the middle:

I will be their God and they shall be my people.

I’m taking each word in turn and reflecting on its significance in the context and for me personally.

I will be their God — I, the Creator of heaven and earth, life giver and life sustainer. I, the God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob. I, Yahweh, the LORD; I AM THAT I AM. I, the I AM who appeared and revealed Myself to Moses in the wilderness. I, gracious and compassionate, abounding in steadfast love and faithfulness. I, both the Judge and the Forgiver of Sins. I, the Redeemer, the Savior, the Messiah/Christ. I—and no other—will be their God.

I will be their God — I am not yet their God, as much as I want to be; they haven’t let me be their God. But I will be; one day in the future, I will be; they will let me, want me, long for me. Not yet, but one day….

I will be their God — Specifically, I will be the God of the House of Israel and the House of Jacob. In that future day when I will be their God, “they” will include Gentiles grafted into that house like a wild olive shoot grafted into an olive tree (see Romans 11:11-24). I will be the God of all those who believe in me, who worship the Christ Redeemer, who reject all other gods. i will be their God.

And they — those same ones who believe in Me—shall be My people.

And they shall be My people — they’re not yet; remember, they haven’t accepted Me yet. They’ve fought me and left me and rejected me and pretended to be me. But one day, they shall be my people.

And they shall be My people — I will claim them and adopt them and love them as my own. I will nourish them, nurture them, teach them. I will lavish my extravagant love upon them. They shall be mine, my very own, and no one else’s.

And they shall be My people — not my peoples, distinct and numerous different groups; but people…one people, one family, one body, one Church…one. Each one unique and special and a treasured possession, but still one people. My people, my children, my dearly loved ones. They shall be My people.

To one who has never known family, never known the passionate, fault-forgiving, undying love of a mother or father, these words are almost impossible to explain. It is difficult to fully grasp the hope that is laced into the words, “I will be their God and they shall be My people.” It’s a bit like trying to explain to a 20-year-old how they will know when they have met “the right one”: you will just know it.

When Jeremiah wrote God’s words the New Covenant, “I will be their God and they shall be My people,” it was still future; it was not yet.

When Jesus Christ brought the New Covenant into reality, it became now and not yet.

One day—when the time is come and The Day is upon us and Christ comes again—the New Covenant will simply be now.

And the LORD will say, “I am their God, and they are My people.” Welcome home.

Several months ago I read

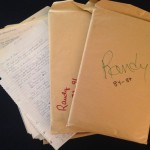

Several months ago I read  I received one of the most unusual gifts ever for my birthday this year. Wrapped in gold paper and tied with a gold ribbon, the package came with a note: “words—no matter when written—are gold, both to the reader and the composer.” High expectations. Inside were four large envelopes, each half an inch thick, with my name and dates from 1981 to 1991.

I received one of the most unusual gifts ever for my birthday this year. Wrapped in gold paper and tied with a gold ribbon, the package came with a note: “words—no matter when written—are gold, both to the reader and the composer.” High expectations. Inside were four large envelopes, each half an inch thick, with my name and dates from 1981 to 1991.

As I write this, I’m sitting in Starbucks working on a paper about engaging the local church in missions (and, interestingly, listening to Chris Tomlin’s “

As I write this, I’m sitting in Starbucks working on a paper about engaging the local church in missions (and, interestingly, listening to Chris Tomlin’s “