What are your feelings about money? When you think about your finances, what emotions course through your veins?

I stepped back into the financial industry at an interesting time: the stock market is down more than 20% this year, inflation is soaring to a forty-year high, and talk of a recession—are we in one? How long will it last? How bad will it be?—is dominating the business news almost as much as the war in Ukraine dominates the global news. Ironically, when I left the financial industry in 2008, the economy was just entering its last major recession.

In between—from 2009 through January of this year—I was a pastor. Much of my work then, and much of my work now as a financial advisor, is the same: walking with people through their fears and insecurities … and their beliefs. What I’ve found is that what we DO is rooted in what we BELIEVE.

Between what we do and what we believe are our attitudes and emotions, which tend to lie along a spectrum with fear and anxiety on one end and happiness and contentment on the other.

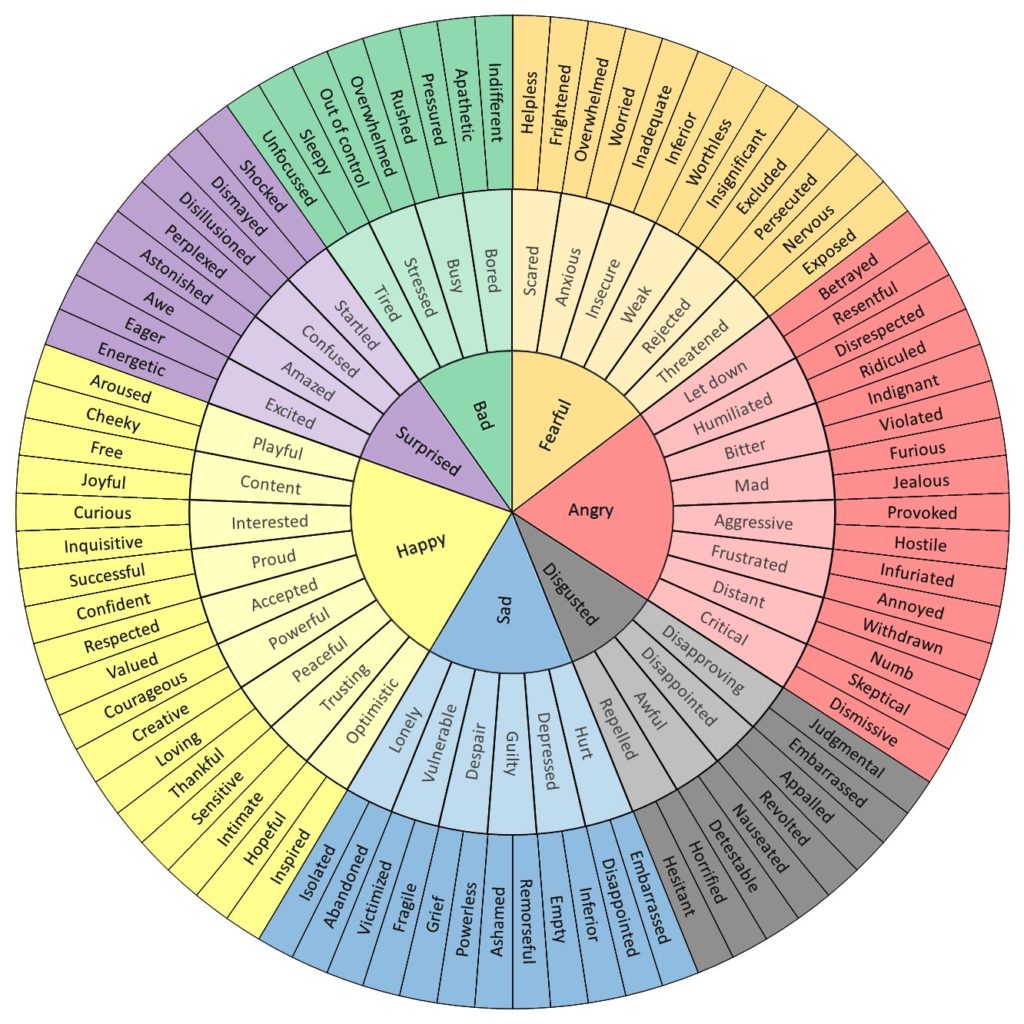

So, where are you? Take some time to ponder your thoughts, feelings, and attitudes about money. Use this feelings wheel if you need help to think of emotions words (like I do). “Fearful” may not be the first word that comes to mind, but words like overwhelmed, worried, or anxious fit, all of which are “fear” words.

If you are or ever have been married, think about conversations you’ve had with your spouse about finances: were they good, easy, hopeful discussions? Or were they filled with dread, fear, stress, and conflict?

Think about your upbringing, as well. What did you hear from your parents and grandparents? Not just the explicit things they tried to teach you, like saving or giving, but also the whispered conversations you may have overheard. (We can hear reminders like “don’t waste food” or “turn off the lights” as messages of scarcity rather than responsibility, no matter how they were intended.)

If you have children, think about the words you hear yourself using with them. What messages might they be hearing. Maybe even ask them what those messages are … if you’re brave!

Spend some time writing down the thoughts, feelings, and messages that come to mind. Then try to identify the underlying beliefs behind those.

In the coming days I’ll write more on this topic. As we come to a greater understanding of ourselves, I hope we can also begin a journey toward greater financial health and freedom … which, by the way, is not found simply in having more money!